What is the most significant Honda of all time? Of course, it must be the CB750. Or any of those incredible 6-cylinder racing bikes from the 1960s. Or the NR750 with its oval pistons. Hang on, it must be the Fireblade?

Actually, no. It’s none of those. In fact, there can only be one most-significant Honda, which also lays claim to being the most significant motorcycle of all time and it is the Honda Super Cub.

Before you all assume that it must be because 100,000,000 (that’s one hundred million to you) have been manufactured, I’m going to have to disappoint you one more time. Yes, any motorcycle that sells in those numbers has to be significant because it must have been good enough to sell in those numbers in the first place. But it ’s not the reason I’m thinking of.

The Honda Super Cub was the brainchild of Soichiro Honda and Takeo Fujisawa; Honda was the engineering and production brain of the company, Fujisawa the finance and business brain. It was Fujisawa who saw that the normal progression in terms of personal transport was from a bicycle to a clip-on engine for a bicycle, maybe to a scooter and thence to a small car. The motorcycle didn’t fit into this timeline anywhere. He wanted to change that.

All Soichiro wanted to do was go racing but Fujisawa was adamant. His idea was a motorcycle that would be everything to everyone, everywhere, whether first or third world, urban or rural. It had to be simple to survive in places with no access to specialist tools or spare parts; it had to address the usual consumer complaints of noise, reliability (both mechanical and electrical) and dirt, and be simple to operate. Eventually, Soichiro’s interest was kindled and he delivered the bike Fujisawa knew was going to put Honda on the map.

A pressed steel monocoque chassis was utilised, with the engine underslung in the middle. The 50cc, four-stroke engine produced about 5bhp and gave a top speed of around 40mph. A low compression ratio meant the engine could run on even the worst quality fuels and it was easy to kick over. Placing it in the middle of the bike meant a better balance front to rear, less unsprung weight on the rear wheel (traditionally, scooters had the engine mounted on the rear swing arm, driving directly to the rear wheel) and allowed larger wheels to be fitted, making the bike seem more like a familiar bicycle. The gearbox was a three speed with centrifugal clutch so no clutch lever was necessary.

The real revolution, however, was the plastic bodywork that hid the mechanicals and the chain and protected the rider’s legs and feet. Lightweight, distinctive and cheap to produce (and replace), the Super Cub was the first motorcycle to use a plastic fairing.

Honda built a huge new factory in order to build 20-30,000 Super Cubs a month! When Edward Turner, MD of Triumph motorcycles, visited the factory, he said that such a huge investment was risky as the US market was already saturated. Famously, however, he also got it hopelessly wrong when he said that the emergence of a new small bike market was good for BSA-Triumph as riders would graduate to bigger models, not imagining that the Japanese would take over that market as well, leaving the British industry dead in the water.

So, whilst the Super Cub could be seen as significant for paving the way for Japanese domination of motorcycling in the US and the rest of the world, that’s also not what I’m thinking of. The Honda Super Cub is significant because of how it was marketed.

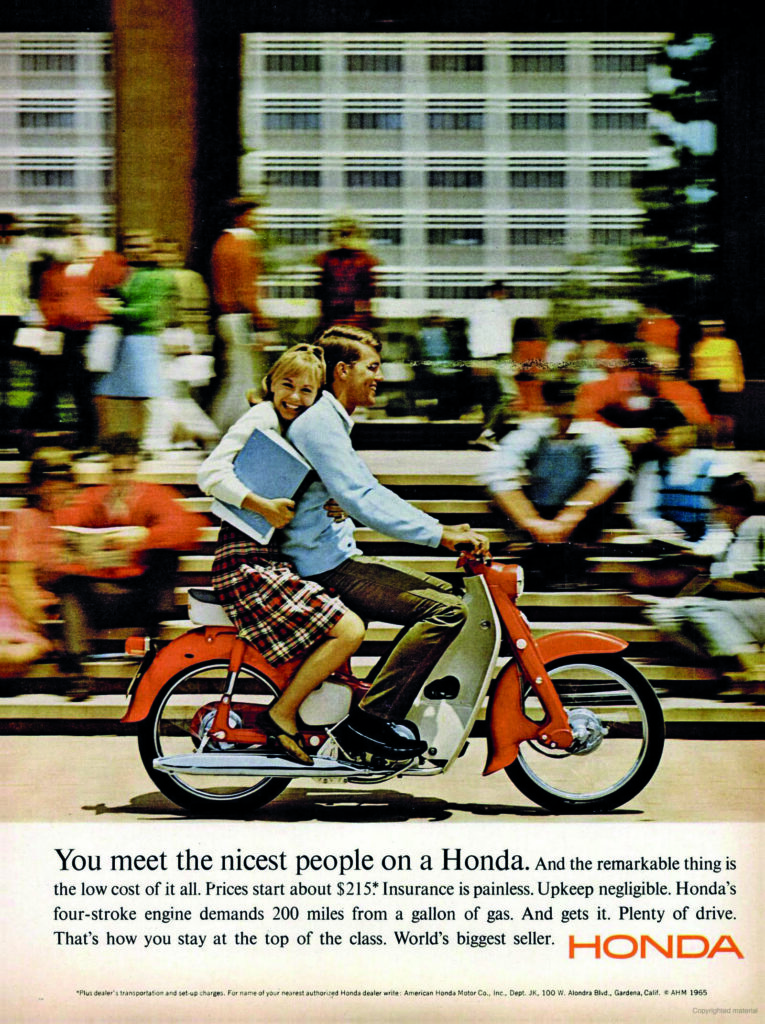

In early 1960 Honda’s advertising agency in the US launched the “You meet the nicest people on a Honda’ campaign. It was so effective that it is still being used as a case-study in business and marketing to this day and is credited with inventing the concept of ‘lifestyle marketing’.

In essence, the importance of the campaign was that is was aimed not at motorcyclists but the ordinary man-in-the-street and, more importantly, the woman in the street! It completely changed the perception of motorcycling and presented the machine as a consumer appliance requiring no mechanical aptitude nor needing an identity change on the part of the rider into a ‘motorcyclist’ or, even worse, a ‘biker.’ As one expert recognised, “the dedication required to maintain bikes of that era limited ownership to a relatively small demographic, often regarded as young men known for their black leather jackets and snarling demeanors.”

The Honda Super Cub was as far from this traditional idea of motorcycling as it was possible to get, while still offering the freedom and practicality that two-wheels permitted. It at once invited you into a world that was not only unthreatening but gave the promise of joining a smart new set and allowed you to stay smart; specific elements of the Super Cub’s design were integral to the campaign, such as the enclosed chain and leg shields keeping clothes clean, and the simplicity of operation.

Honda broke completely new ground with the campaign; rather than trying to convince traditional male buyers to switch to Honda from other brands by taking the same macho approach, the company sought to improve the image of motorcycling in general and attract new riders; in effect, creating a whole new market for themselves in which there were no other players at the time. It was as revolutionary as the bike itself.

At first, Harley Davidson was offended at the implication that H-D riders were not ‘nice people’. Seeing the success of the campaign, however, it was soon copying the concept with its own ‘Young America’ adverts. Imitation really is the sincerest form of flattery, it seems.