Nick’s note: Alex Hatfield takes the reins this week to talk about consistency with weapons: rifles and motorcycles. Handled well, they are safe. Handled poorly, they are deadly. Alex is a Champions Certified Coach (3C) and heads into his rookie roadracing season with the USBA while working on his law degree.

Alex Hatfield competing at the 2015 International Sniper Competition. (Alex Hatfield/)

The instructor glanced around the room, his rapid-fire lecture paused just long enough for our exhausted hands to finish taking notes on our equipment, history, and employment. “Now write this down,” he said. “Consistency equals accuracy.” It was day one at the United States Army Sniper School, and I had just written down a life-changing lesson, summarized in three words.

In the sniper community, accuracy is paramount. The primary mission of a sniper is to deliver long-range precision fire on key selected targets and targets of opportunity. The secondary mission of a sniper is the collection and reporting of battlefield information. The accuracy of our fire or reporting is a very real life-or-death issue. Miss a shot and your position is given away, an IED is planted, a buddy gets shot, or you get shot. Pass along bad information and an entire unit could be decimated (Anzio in World War II is a perfect, gut-wrenching example). The best way to achieve consistency is to reduce variables. Of all the variables we need to account for, the most important variable is the sniper.

If we can find a way to reduce ourselves as a variable, everything else becomes a math problem.

Backward planning helps: Start from the goal, work your way back. As sniper candidates, our goal was to be accurate. To be accurate, we must be consistent. To be consistent, we must reduce variables.

Shortly after arriving at the schoolhouse, we were given a reality check: There is no “secret sauce” to hitting targets beyond 300, 500, or even 1,000 meters. The difference between a trained sniper’s shot and a weekend shooter at a range is really just one thing: the degree of input application.

RELATED: Motorcycling Consistency: Part 1

Where a novice shooter might break the trigger by simply flexing his finger, the sniper smoothly builds pressure directly toward the stock. Both shooters have accomplished the same thing; the rifle has fired. Both shooters used the same muscle groups to achieve this, but the sniper is hitting the 1,000-meter target, while the novice is barely ringing steel at 100 meters. Why is there such a difference?

At 100 meters, not much matters when it comes to shooting a steel plate. There really is no wind to calculate for, no issues with determining target size, negligible Coriolis effect (deflection due to the Earth’s rotation), ballistic coefficients are just numbers on a box, and density altitude is largely irrelevant. In short, the 100-meter shooter becomes 90 percent of the variable influence on each round fired.

At 1,000 meters, a sniper must account for a laundry list of variables, and each of them has an influence on the shot. The Coriolis effect might influence 5 percent of each shot, the wind might oscillate between 40 and 80 percent during gusts, and so on for each variable. In order to consistently land rounds on the target, the sniper needs to reduce his own unintended influence on each round as much as possible to allow time and space to calculate for, solve, and adjust for each variable and achieve first-round hits.

Here’s where it gets interesting. Ask the sniper to shoot the 100-meter target. Round after round will impact in the same square inch of the steel, almost exclusively limited by the inherent mechanical accuracy of the rifle and ammunition. While the novice shooter may strike the plate repeatedly, the strikes are inconsistent. Why the difference? While both shooters are responsible for 90 percent of what the round does, the sniper’s actual influence on the round is minimal for two reasons: The sniper is consistent in his inputs, and his degree of application has much stricter tolerances.

“Cool,” you’re thinking, but what does this have to do with motorcycles?

Studying the art of going just a little faster. (Photo courtesy of Bluepants Media/)

“Consistency equals accuracy” changed much more than just my approach to shooting; as it turns out, consistency is the key to being successful at many things in life, motorcycles among them. While our definitions of accuracy may vary, the concept remains unchanged. Develop consistency in the little things, and watch the bigger things improve. As Kyle Wyman once told me, “How you do one thing is how you do everything.”

Watching MotoAmerica, WSBK, and MotoGP riders click off lap after lap with tenths-of-a-second splits is easily one of the most beautiful examples of consistency in the world. The laser-like precision of riders as they recognize and react to markers or touch their knees (or elbows) down at the exact same spot on the tarmac every single lap is mesmerizing.

Much like a rifle, a motorcycle is designed by expert users and responds well to certain inputs. Like long shots, everything matters when you add speed. Like snipers, these national and world-class riders are consistent in their inputs and have extremely strict tolerances for those inputs.

I spoke with Nick Ienatsch, the founder and head instructor of the Yamaha Champions Riding School, about the similarities between sniping and riding. Nick said that there is one fundamental parallel between the two: “No two scenarios are the same.” Thinking back on both past rides and deployments, I had to agree. “The only hope for consistent success,” he continued, “is what the shooter/rider does. Our consistency removes one variable. If that consistency is best practices, then we succeed. If that consistency is second-best, then we are mediocre and intermittent.”

Mediocrity as a rider or shooter is evidenced by two things: loose tolerance of inputs and inconsistency. This may appear as sloppy trigger pulls, clunky braking, missed shifts, fumbled groupings, or failure to control fork rebound.

Looking on jealously as Nick Ienatsch enjoys a warm jacket on a cold day. “Man, those old guys are smart…” (Yamaha Champions Riding School/)

In both dangerous professions and dangerous sports, mediocrity kills. The same MotoGP, MotoAmerica, or WSBK riders who are pursuing consistency are statistically much safer than the mediocre rider out exploring twisty roads on a Saturday.

One of the two leading causes for death on a motorcycle is simply running wide in a corner; a rider-error mistake. While the stakes of being a mediocre racer are typically sliding across some tarmac in a leather suit and a very short career, the stakes of being a mediocre rider on the street are all too often an ambulance or a casket. Where does this acceptance of mediocrity for street riding come from?

The motorcycle education industry has largely failed to instruct students in best practices when it comes to the fundamentals and processes of riding. Riders are taught unsafe and outdated techniques in the worst environment possible: new rider courses. I have seen (and taught, mea culpa) curricula that forbade covering the brake, mandated straight-line braking, and studiously avoided demonstrating what smooth control input looks or feels like. These bad habits are drilled relentlessly by well-intentioned instructors, but the fruits of their labor are generally riders who will never attend another class. Good habits like trail-braking, covering the brake, and weighting the inside peg are flatly rejected as “racing techniques” that are “unsuitable for street riding, especially to new riders.” Even the most well-intentioned and enthusiastic new riders can only achieve mediocrity if they are never taught the best way to ride a motorcycle.

Without intervening early in their education, these new riders are doomed to a Sisyphus-like existence: Rolling this stone of mediocre riding up a hill, wondering why riding is no fun until they get hurt or quit. If the student crashes and quits after attending their basic rider course, the instructor is likely to shrug it off as a lack of experience instead of lobbying for a change to the organization’s curriculum.

Hatfield coming to terms with his mediocrity after crashing his very first motorcycle, a week after graduating his basic rider’s course. (Alex Hatfield/)

There is a common—and flawed—saying that pervades the riding community: “Practice makes perfect.”

Consistently applying poor technique will inevitably lead to poor results. Practice does not make perfect—practice makes permanent. The rider who is consistently snapping on the throttle, grabbing a handful of brakes, exclusively braking in a straight line, or throwing a bike into a corner is not reducing himself as a variable. These habits don’t really matter at parking-lot speed. Like shooting our 100-meter target, not much matters when we ride slowly; we have lots of traction and not much to worry about. However, as the pace picks up or available traction decreases, everything matters.

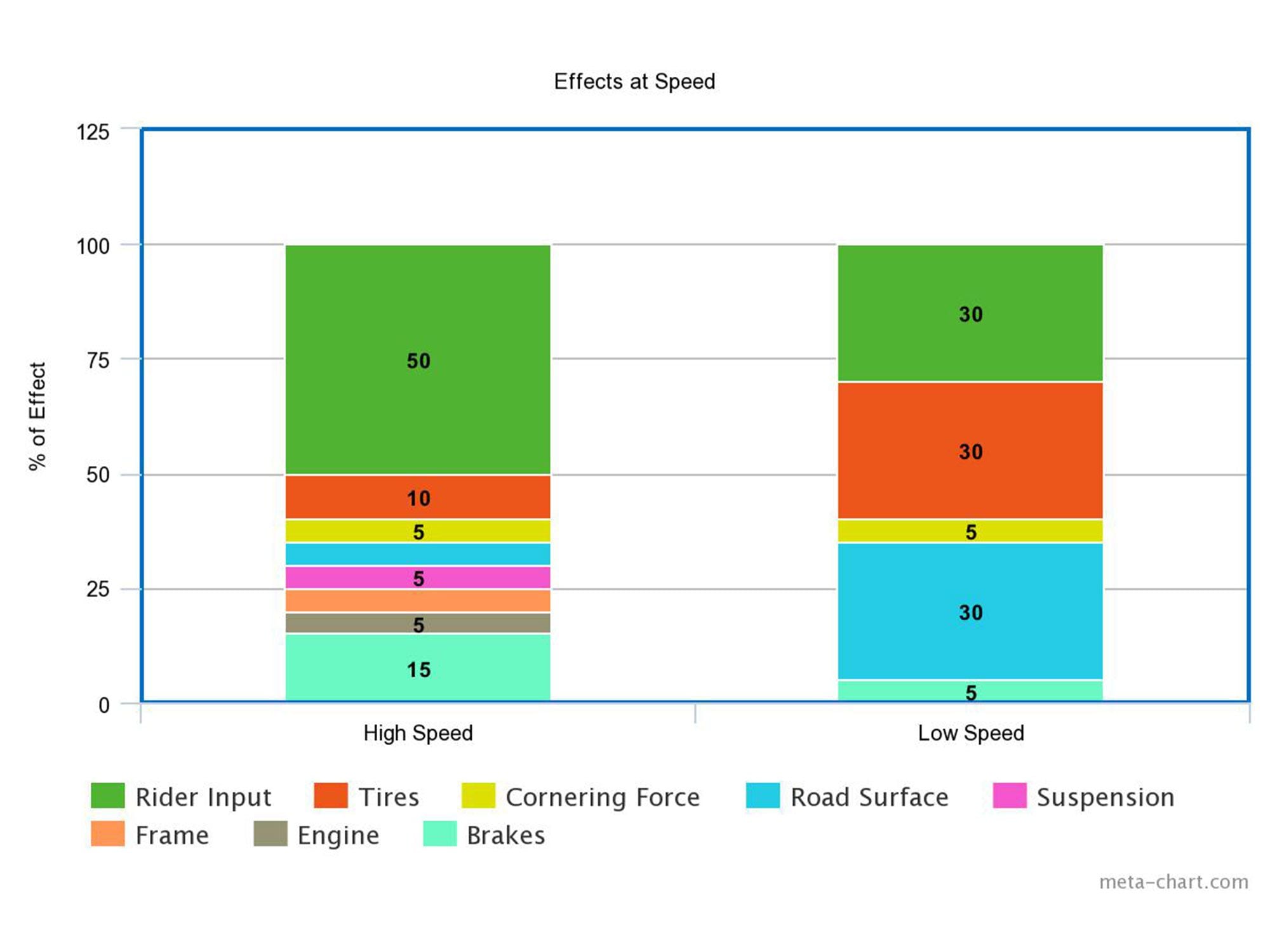

In Figure 1, we see that at high speeds, the number and effect of variables increases. Because there are more variables and because the effects of the rider’s inputs are magnified, an expert rider must work to reduce himself as a variable. (Alex Hatfield/)

When we start going faster, our inputs become magnified.

A ham-fisted twist of the throttle results in a highside. Abruptly releasing the brake lever reduces our front tire’s contact patch and we lowside. Just like the sniper engaging the 1,000-meter target, we must work to reduce our unintended input on the motorcycle. By refining our degree of application and tightening our personal tolerances for inputs, we can overcome mediocrity. Working toward consistent inputs, we can effectively reduce ourselves as variables. As we achieve this consistency, our riding “accuracy” increases; our bike is exactly where we want it at all times, we stop smoothly and in control wherever we need or want to, and we enjoy every ride.

Perhaps more than anyone else on this side of combat, street riders are regularly exposed to wildly fluctuating conditions. If we continue to accept mediocrity in our own riding, we will continue to be a variable on every ride, on every street. The rider who practices good technique and becomes consistent in loading the tire before working the tire, who spends hours mastering the fine motor control needed to sneak on and release the first and last five points of throttle and brakes will have a safer, more enjoyable life on a motorcycle than the riders who accept the boulder of mediocrity. This safer rider understands how their inputs affect the motorcycle, is intolerant of their own sloppiness, and is consistent in their inputs. They can add as much or as little speed as desired or required and risk less in doing so.

By reducing themselves as a variable, these safer riders can enjoy riding for many years to come. However, not many riders are even aware of their impact on the motorcycle—much less how to correct it. The vast majority of riders will never step foot in a classroom dedicated to riding after they graduate their basic rider course. When I taught for a basic course program, the return rate of students after graduating their license-waiver course was less than 10 percent. In order to grow our sport and industry, we need to focus on eradicating the problem of bad habits, abrupt inputs, and mediocrity where it begins: basic rider education.

More next Tuesday!