How do you picture a motorcycle designer employed by a major manufacturer? You wouldn’t be wrong if you thought of a composed person in a suit, as ready for the boardroom as for meticulous work in the clay studio; they exist. But imagine instead a large bearded man, smiling easily without self-consciousness, who opens like a spring flower during spirited discussion of frame or gas tank or exhaust pipe shapes. Imagine further that since childhood he has endlessly taken in images, drawings, scenes from real life, and the shapes of all familiar things, becoming a tangy compost heap from which arise forms that speak without words. That is a fair introduction to Ola Stenegärd, director of Product Design at Indian Motorcycle. He was at BMW for 15 years before that and, earlier, at SAAB three years. Now here we were talking together by video link.

Stenegärd said when he was hired in 2018 his design group was told, “You guys are gonna design the new Chief.”

A new design can’t just burst into being from nothing. How does it happen?

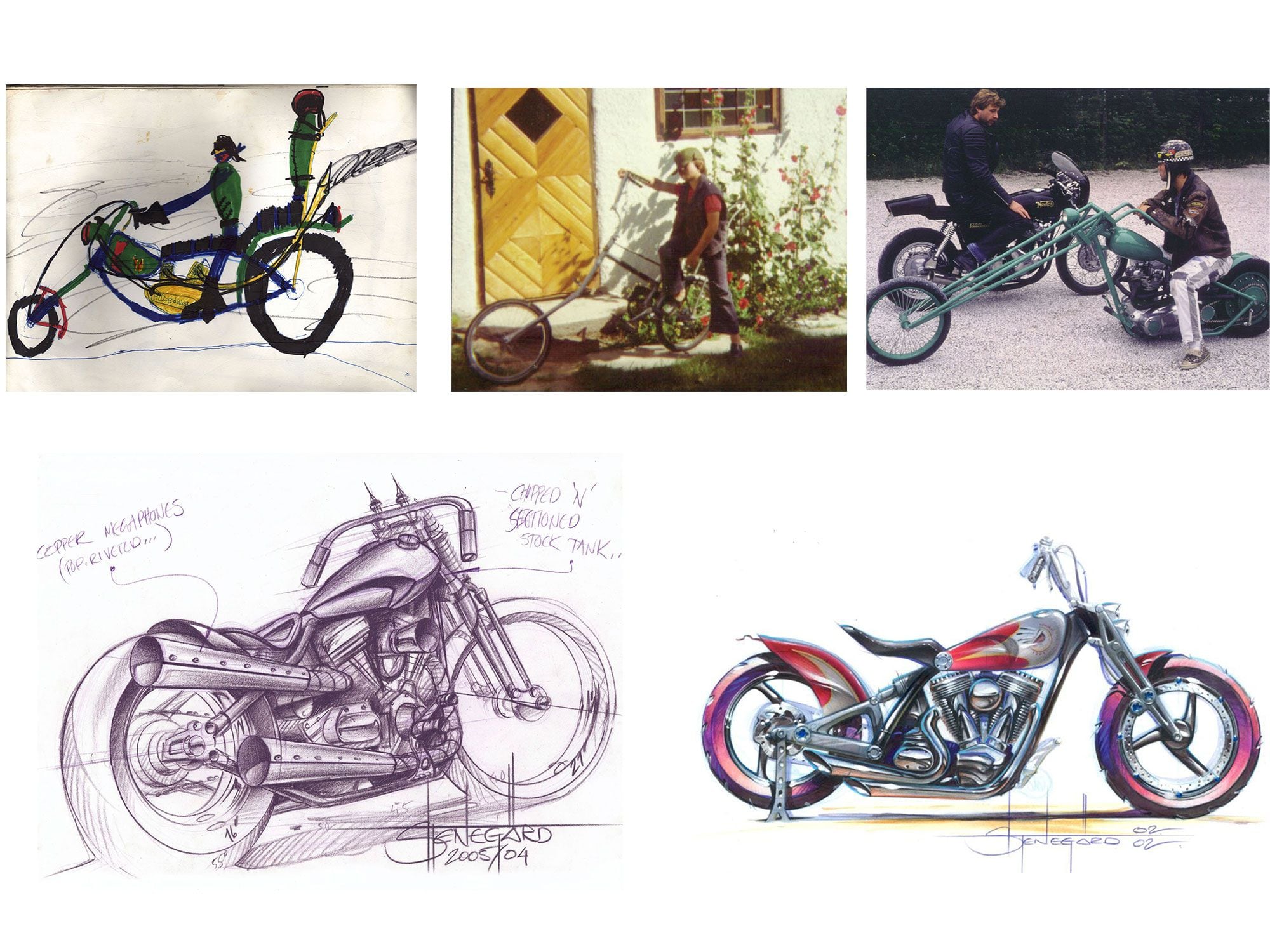

“It helps to grow up in that scene—riders, builders, enthusiasts,” Stenegärd says. “And bikes—customs, bobbers. I’ve always been looking at all American heavyweights. The custom scene is always driven by the street.”

And Stenegärd has been building with his own hands in his well-equipped shop in southern Sweden.

I’d looked at the images of the new Chief, now come into being 100 years after the original of 1921. To me it has big strong ox shoulders, mass forward, lunging. It is filled up, dense. Then I had a question.

Stenegärd seems to have a foot in each of two camps. He had to design a bike whose visual language stops people and sucks them into a world they want to explore. But his design couldn’t be so well-integrated, like Harley-Davidson’s V-Rod, that custom builders ignore it. Change anything on the V-Rod and it looks wrong. How could he achieve that?

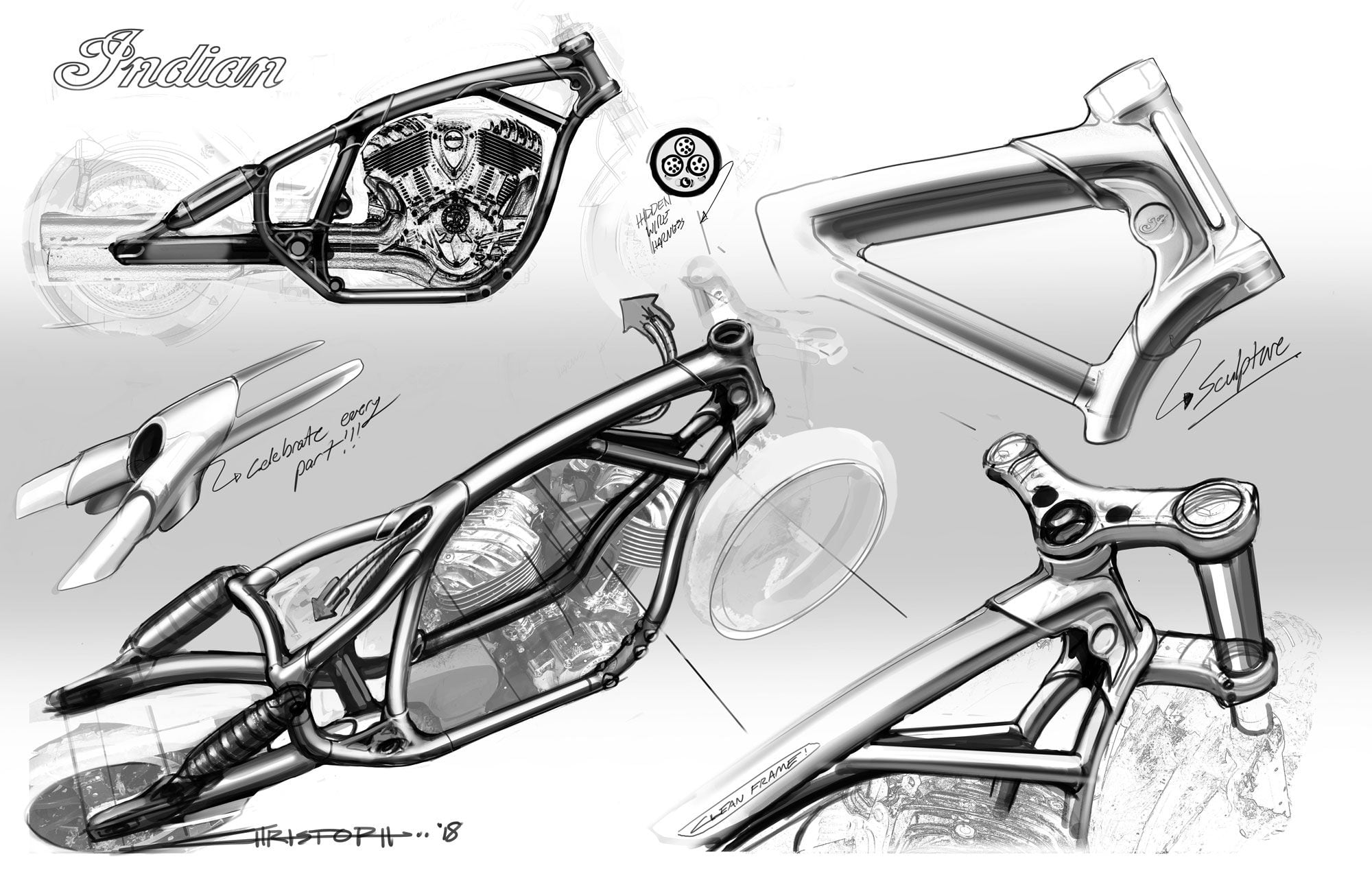

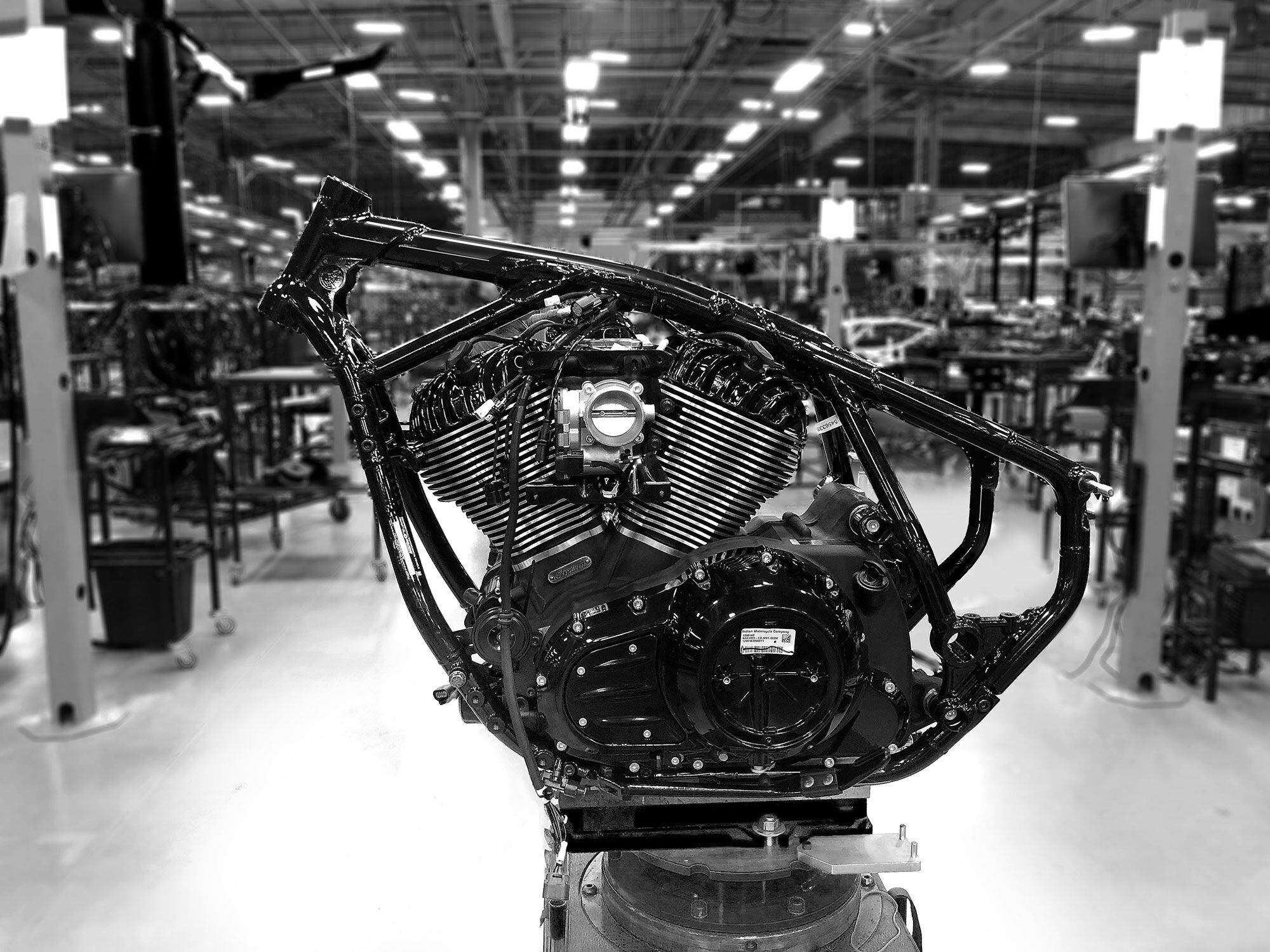

“We all build bikes ourselves,” Stenegärd says. “This is part of the story. Everything starts with the frame. No pressed steel hiding where you can’t see it. Nothing ugly appears when you lift the tank. The frame needs to be a piece of art by itself—on a pedestal. But a superbike has to be super-integrated.”

Next he said something whose down-to-earth practicality delighted me: “We build on a table. You clamp the wheels to the table, set the engine where it belongs, and then you start bending tubes. And bending tubes in real life, versus bending tubes in CAD, are totally different.”

My delight was in the image of the director, sliding curved tubes out of the bender, trying them in place, and looking.

When a new bike is in planning stage there is competitive drawing. Stenegärd said, “I looked at the sketch competition. The only one with the bones in the right places was Rich Christoph. We just nerd out on the same things.”

The new Chief’s frame is steel. Why?

“For us it’s not even a question. Customizers have to be able to cut and weld these things, and you can’t do that with aluminum [Indian’s big tour bikes have aluminum frames]. A steel frame was the only way to go.

“When all of that stuff sits right, the frame looks right by itself. The cables are all inside the top tube, so there’s nothing in the way when you take the tank off.

“The bones gotta be in the right places. In the early days they didn’t have designers, but the pieces they made still look right today. The cast frame lugs [joining the tubes of classic American bikes] were given their shape by pattern-makers. Lugs have to have a right look. I have old drill presses and lathes in my garage. The pattern-makers in the foundries that made those machines knew how to make things look right.

“We tried to take this bike back to those roots.”

Now he was making his point: That the elements of the bike must each be rewarding to behold by themselves, not just slickly integrated like the jigsawed parts of a picture puzzle.

“It’s super-complicated to make things simple,” Stenegärd says. “CAD makes it too easy to make really complicated things. Keeping it simple has become so complicated.”

Writers learn this same lesson. It’s easy to write long, but it takes concentrated thought to write short, simple, strong statements. I felt a contagion of excitement as Stenegärd became steadily more animated, speaking more quickly and intensely.

He described what he called “The Three Flavors” of the new Chief: Chief, Chief Bobber, and Super Chief.

“There’s a lot of detail stuff that’s so good. Super Chief—it feels like it belongs in The Wild One. They had girls’ bike gangs too, back then—super cool! After the war all these women, these welders and machinists, weren’t willing to go back to the kitchen.

“Super Chief is the bike you ride to Hollister, take off the bags and windshield and do it. Then you put it all back on, ready to ride to work Monday.

“Bobber—this takes us into the mid-’60s and the biker B-movies. It should be that bike. It was designed with a solo seat but now we offer it as an accessory.

“Chief Dark—the ’70s and ’80s—that’s like the latter-day builders who are now using performance parts, mid-mount pegs, narrow bars, 19-inch cast front wheels—super bare-bones.

“It’s almost become my mantra—keep it simple, keep it clean. The more you take away, the more important it is to simplify the bones.

“I’m just babbling now because I’m so excited by this stuff.

“These bikes are made to ride hard. They all look badass—you look really good riding them. They have that Jesse James look. That’s how you want to sit on a bike.”

Twice he’d referred to a 1950s image of Hells Angels founder Sonny Barger on a custom Panhead. Salesmen may think motorcycling is recreation, a way to kick back. To riders, it’s life.

An hour and a half had passed quickly. This was not work. We wanted to keep the surprise of all these associations coming. We promised to be in touch soon.

As the link ended, Stenegärd said, “If it isn’t fun, it isn’t good.”